One of the writer’s favorite things is the villain.

I’m not even sure why, but almost every writer I know loves

developing villains, creating them, and watching them do evil things in order

to thwart the hero.

While avoiding getting into the psychological ramifications,

it does leave a wide opening for discussions and blog posts. I’ve posted before

about villains, about minor villains, about conflict and stakes and all sorts of

things down the vein of villains. Today I’m going to peer back into that vein

and see what else I can pull out.

While avoiding getting into the psychological ramifications,

it does leave a wide opening for discussions and blog posts. I’ve posted before

about villains, about minor villains, about conflict and stakes and all sorts of

things down the vein of villains. Today I’m going to peer back into that vein

and see what else I can pull out.

Oh.

The title says world blip.

Guess I better find something in there that is worldbuilding

related.

Twenty Minutes Later…

AHA

I found something.

There are a lot of “dark sides” in movies and books. From

the literal Dark Side of Star Wars to

the symbolic “shadow” in The Lion King

where the lion does not rule, there are dark places. Places villains live. Evil

lairs, mountain fortresses, piles of skulls, random candlesticks, and corporate

skyscrapers that look evil just by existing.

Here’s the deal: each

and every one of those things screams

evil.

Why?

Most “villains” don’t think they’re evil, so why do their lairs

look like that in movies and books?

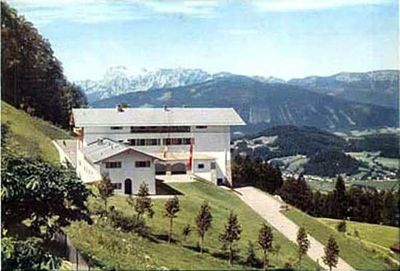

Like take the classic example of a villain actual history:

You know what that is?

That’s Hitler’s house.

Well, one of them.

It doesn’t look evil and full of vileness. Not really. More like…

old fashioned, and that’s because it was a while back.

It doesn’t look like the home of one of the most reviled men

in all of history.

What about this one:

That’s Stalin’s house, Kharkov.

It looks rather refined to me, not super dark and

evil-looking. Stalin killed a lot of people. A lot of people.

There are a lot of clichés in the development of evil

places, so let’s explore those, and explore why those clichés are so often

chosen and used.

Describing the Land of Evil

This is one of the most common clichés known among men. The

Land of Evil. I’m not sure who started this, maybe Tolkien did. Maybe Mordor

inspired a slew of books that use lands of desolation and darkness to notify

that “villain lives here”.

What makes this cliché so common, and so useful?

It shows without

telling. When you describe a dark, evil setting by showing, you also show

that the villain is evil. It’s a backdoor sort of showing. It’s implicit. If

they place they live is evil, so must they be. This, however, is also a copout. It’s lazy. How easy is it to

describe black rocks, skulls, and angry clouds? Very. I could easily describe any

of those things, complete with looming towers with jagged tops and red lights

winking through slitted windows, the stark white bones of defeated enemies

littering the jaded plain before them, without having to think very hard. I

mean, I just came up with that one without having to think at all. My phone

actually lit up while I was typing that sentence and I glanced over at it while

writing the middle portion.

That’s how easy it

is to write a setting that sounds

evil.

Everyone knows what evil settings look like, nowadays.

But what if???

What if we had villains who didn’t look anything like that?

Villains who are evil but don’t think they are? Now, there’s nothing

wrong with villains who live in evil places. They are fine. They work. But they

aren’t always true to life.

Some villains live in lavish mansions. They live in palaces

and or in normal-looking houses.

How, then, do we build these things in such a way that the

world still shows their villainy?

Undeserved Fortune

If undeserved misfortune is the way to a sympathetic hero,

then Undeserved Fortune is the way to a hate villain. When a villain’s hideout

is dark and dreary, we’re not jealous of them. We just think they’re evil.

The villain who lives in a mansion while the people who

slave for him live in squalor?

We detest him.

The villainess who dines, sleeps, and lounges in luxury

while ordering the destruction of people’s homes for her own gain?

She is despicable.

There is something about undeserved fortune that makes

readers writhe. We hate it when the

hero has it (Deus ex Machina), and we hate it when the villain has it (we also

happen to love it, in this weird sort of paradox where we love the villains we

hate).

When you build the land your villain rules over, give them fortune they do not deserve, and

give those around them misfortune they do not deserve. This juxtaposition

creates in your readers a mindset of “they’re the cruel person, the rest are

just mistreated and need to be liberated”, without having to tell them “this

person is evil”.

Let’s take a moment and recognize that I’m not saying wealth is evil here. This isn’t

a rant against the 1% or whatever. Some of those people are actually nice. In

fact, your villain doesn’t have to be (and often times should not be) incredibly, incredibly wealthy.

Wealth is by comparison.

If everyone in the world had five billion dollars right now,

it would be the same as if we all had ten dollars. Equality of wealth doesn’t

create riches: it creates a new equilibrium.

Therefore, your misfortunate characters can have ten dollars

in their pocked and the villain has a hundred, and it will seem unfair, evil,

and unjust.

People are weird that way.

“Auras” vs. “Reality”

If the villain’s realm is volcanically active and dark all

the time, we’ll see that reality as evil.

Cool.

What about more inventive settings? What makes the luxury

suite of a hotel evil compared to the

janitor’s closet?

Or what makes the janitor’s

closet evil?

I like to call it an aura, and I’m not trying to offend

psychics out there: this is a word I’m stealing from you and you can’t have it

back.

What is this aura? You

create the aura of a place by the words you use. Words have power, and describing

the places you develop goes a long way in creating the presence characters and

readers feel. If you use the right

words, you can make a janitor’s closet seem like the second circle of hell.

What words are these?

Well, it depends on the place. Generally speaking, terse sentences, staccato description, and

slightly-off words can create a sense of wrongness in the reader. Words

that don’t quite seem right, but no one can pinpoint why, sentences that end

seemingly too soon. A touch of reluctance.

I’m getting all prose blip on you now, but this is important:

word choice for showcasing your world is

vitally important.

Implication, Not Proof

One thing that a lot of people seem to miss when it comes to

describing their villain’s lair is this: the

description of the lair does NOT automatically make us think the villain is bad.

It makes us know they’re evil, but we

don’t feel it until you prove it.

Actions speak louder than words, and actions speak louder

setting.

Giving the villain’s setting power and vivid description

creates strong implication that can

then be followed up with obvious proof

to send an impactful message.